No, folks, there isn't an ‘autism’ ‘epidemic'...

We speak about autism as if it's a real biological phenomena. It isn't.

If you'd been a chemist in the 1700s, you'd likely know about phlogiston. A fire-like chemical element, phlogiston supposedly permeated all flammable substances, explaining - among other things - why plants get smaller as they burn.

Phlogiston, along with the classical theory of elements that preceded it, has now been consigned to the bowels of history. But, for a century, it held sway as the primary explanation for chemical processes we now know to include rusting and oxidation.

One of the interesting things about phlogiston is how the theory died, growing more vague and complex as it struggled to incorporate new science that challenged its key assumptions. Frustrated, in 1783, French nobleman and chemist Antoine Lavoisier even argued:

"chemists have turned phlogiston into a vague principle, one not rigorously defined, and which consequently adapts itself to all the explanations for which it may be required [...] it is a veritable Proteus changing in form at each instant."

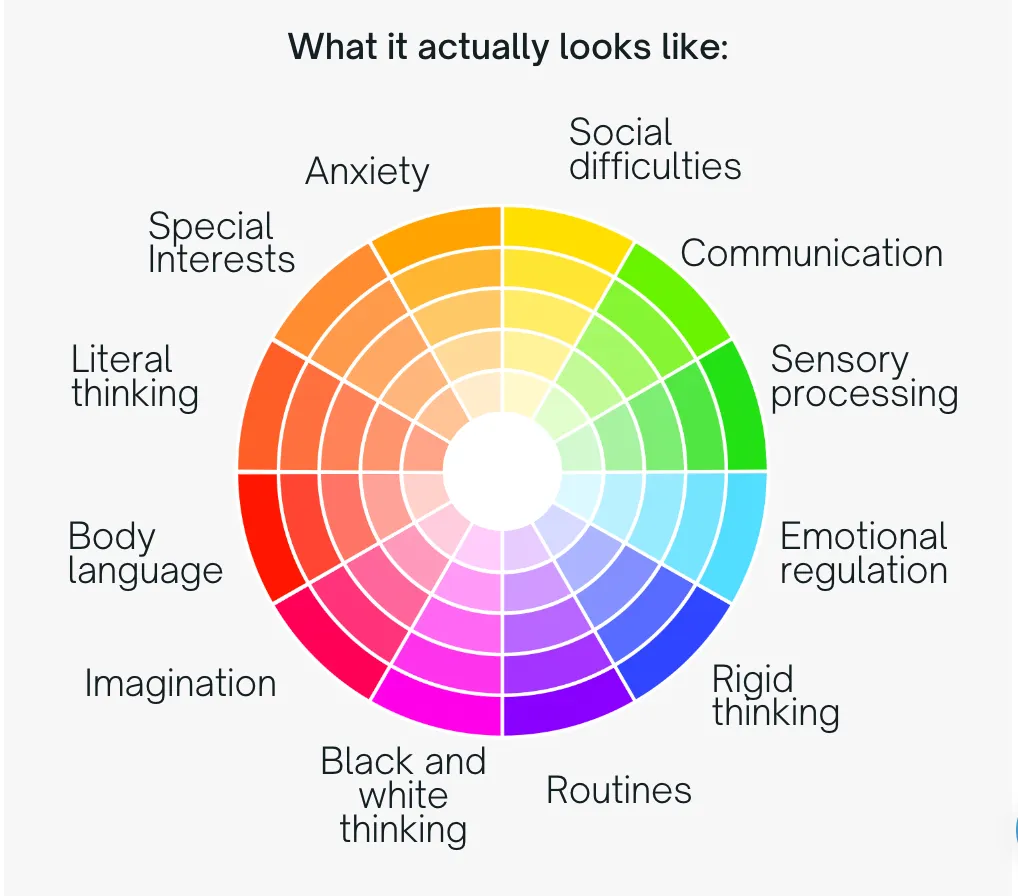

He could have been talking about autism, a 'spectrum condition' that somehow encompasses everything from social anxiety to light sensitivity, and everyone from Elon Musk to Rainman. There's even an expression 'if you've met one autistic person, you've met one autistic person', which is about as vague as it sounds.

Well, what about the DSM-5?

Now, if you've any familiarity with autism, you'll probably be wondering "but, what about the DSM-5?" DSM stands for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and is the internationally-accepted manual for the classification of psychiatric conditions, including autism.

The latest edition, DSM-5, classifies autism as a child displaying two of three types of deficit in social communication, including:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions

- Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication

- Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers

Plus two out of any four patterns of behaviours, including:

- Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

- Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day).

- Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

- Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

There's two things I'll note here:

First, you don't actually need to be socially awkward to get an autism diagnosis. You can line up toys, have a pathological hatred of (the sound of) hand dryers, whole body tics AND be a total charisma fountain with literally tens of friends. You will get a paediatric autism diagnosis, regardless (this, by the way, is Smaller Boy);

Second, the clinician is looking for patterns of behaviour. Thus, if a child in the paediatrician's office and hand flaps, the doctor doesn't investigate WHY they're doing this. They will just put a tick in the 'stereotyped or repetitive motor movements' box and move on.

Now, this wouldn't be a problem if the DSM-5 behaviours all described the exact same brain disorder. And, for the past few decades, clinicians and scientists assumed it was the same brain disorder. There's nothing stupid about thinking that either. Multiple diseases can be diagnosed from a couple of symptoms, as we discovered when Smaller Boy was blue-lighted to hospital with croup.

If you've met one diabetic person, you've met...

Autism, however, is turning out to be more like fever than croup. Or, at least, that's what Lynn Waterhouse, an emeritus professor and director of the Child Behavior Study program at the College of New Jersey, argues in her book Rethinking Autism: Complexity and Variation.

All the research to date... suggests... that “Autism” is not one disorder or many “Autisms” but is a set of symptoms. The heterogeneity and associated disorders suggest that autism symptoms, like fever, are not themselves a disorder or multiple disorders. Instead, autism symptoms signal a wide range of underlying disorders.

Fever is the body's immune reaction to a virus, whereas 'autism' isn't always pathological. And, for that reason, I prefer using the analogy of taking your child to the clinic due to drinking an unusual volume of water. You're expecting the doctor to run some blood tests, but - instead - they simply hand you a leaflet on 'Water Consumption Spectrum Disorder' (WCSD) and send you home.

You might be lucky. Your child might just get unusually thirsty in hot weather, a trait inherited from grandparents and, although mildly annoying, they're going to be absolutely fine. Alternatively, they might have Type 1 diabetes and die a few weeks later. Or they might be like my elderly dog, who was recently diagnosed with Cushing's Syndrome, where the outcome will be more mixed.

Trouble is, you've got no way of telling which. And, if you imagine the social media conversation that would develop around WCSD, you'd have one group of parents screaming, "we need to end the fatal scourge of WCSD forever! We need to investigate the rectal insertion of tapeworms! We need to invent whole new words to describe our child's condition. Only Robert F Kennedy Jnr can save us now!"

....And a whole other group handing out branded Stanley cups.

Like a fish on a tricycle...

In fact, the online conversation between autistic adults and parents of autistic kids is even worse than I've just described.

Water Consumption Spectrum Disorder (WCSD), were it to exist, would be quite a simple condition, with similar symptoms and behaviours. The poorly-understood neurodevelopmental conditions currently tossed into the 'autism' bucket are so wildly different that even parents who think their children are similar are talking about completely different things.

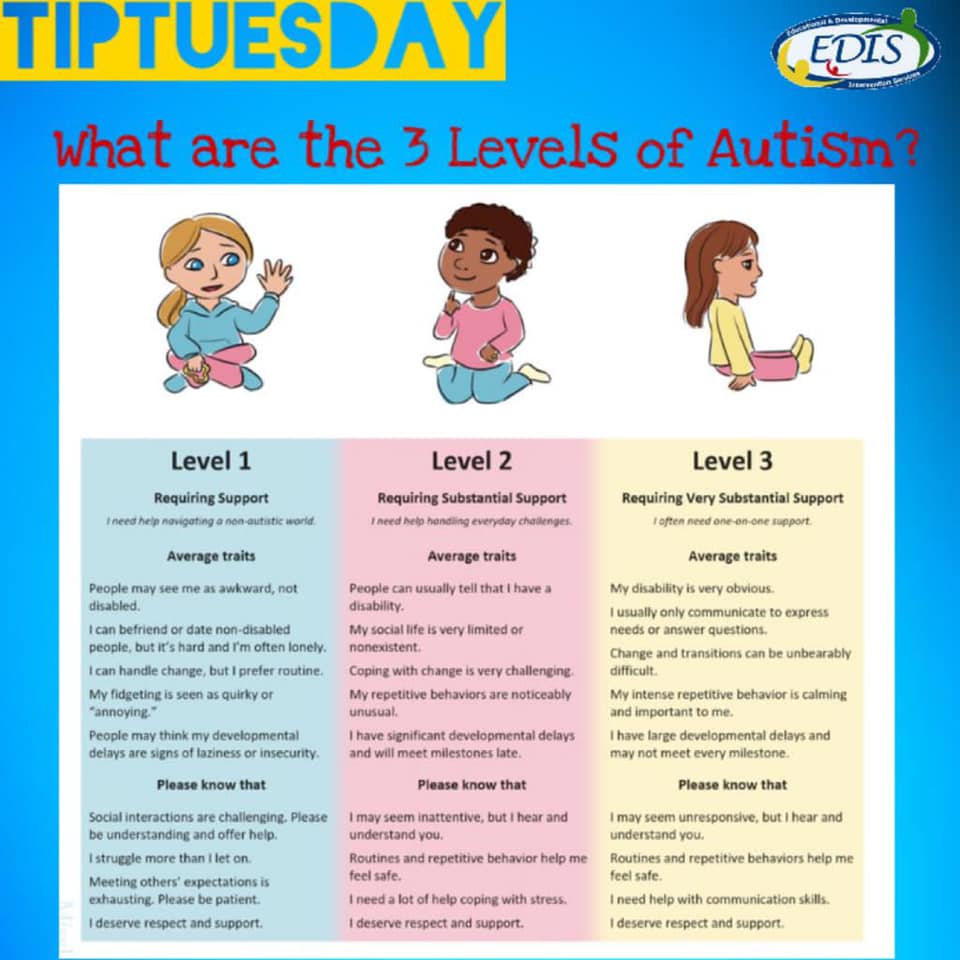

Children diagnosed autistic in America get assigned a 'Level' of severity, which varies from '1: Requiring support' to '3: Requires very substantial support'. These support levels are already bollox on a trike. To put this in context, Bigger Boy spent two years with an autistic classmate, Y, who had the mental age of a toddler. Y was incontinent, completely nonverbal, and... had lower support needs than my own son (suck on that, Profound Autism Moms!).

If you've read my book reviews or Rotterdam travel guide, you'll know the only way Bigger Boy is 'profound' is 'profoundly gifted'. But he's so hyper-sensitive to light, sound and movement that, in a group of 30 shrieking, paper-waving under-sixs, his sensory issues caused more disruption than an intellectually-disabled classmate weeping quietly in a corner.

Needless to say, Bigger Boy is now home educated and has negligible support needs - provided we don't step outside.

Even among parents who identify their children into new sub-categories, such as Profound Autism, defined as an inability to self-advocate and needing 24/7 care, it's obvious they simply don't have the same underlying brain disorder. Sarah, who blogs at Inchstones, has two kids, Millie and Mack, who - from what I can tell - have severe apraxia that traps their intact cognition in bodies that won't - and can't - cooperate. In contrast, Eileen Lamb's son, Charlie, has such severe intellectual disability that he's been known to swallow screws.

Neither Millie, Mack nor Charlie can speak, and they all need 24/7 care, but it's hard to imagine a unified genetic cause, or even a shared brain mechanism, behind such different disabilities. It's not even possible for different families to truly understand or, sometimes, even talk civilly to each other.

To add to the complexity, there are now autistic adults who, despite high support needs, are able to share lyrical and passionate thoughts using iPad/tablets.

Inside Our Autistic Minds by Chris Packham on the BBC, Murray

Grasping more than an elephant

The result is that families, and scientists, are often acting out the parable of the blind men and the elephant. Everyone's investigating, or advocating for, their own pet theories or the parts of the elephant they've personally grasped. However, it's not even one elephant - it's more like feeling up multiple zoo animals, as there's likely hundreds, if not thousands, of neurodevelopmental conditions categorised under the autism umbrella.

As of today, "extensive genetic studies have revealed hundreds of genes linked to autism" along with "certain environmental influences [that] may [also] increase autism risk". "No meaningful subgroups of autism have been discovered" and "there is no drug treatment that directly addresses the symptoms."

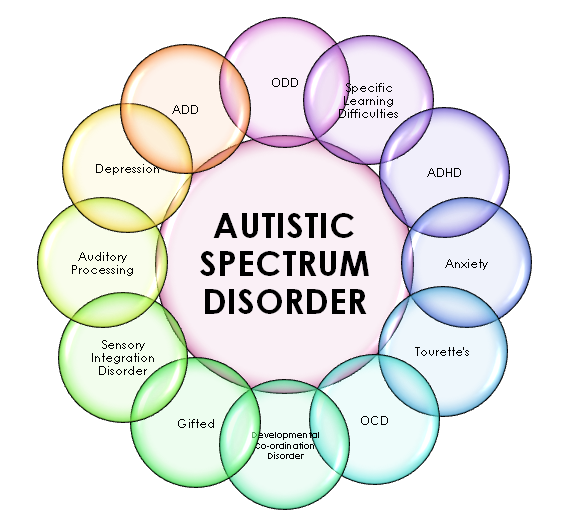

Moreover, autism isn't even a standalone diagnosis. As Lynn Waterhouse writes in Rethinking Autism:

"the expression of autism nearly always occurs with one or more additional non-diagnostic symptoms including but not limited to intellectual disability, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms [ADHD], perceptual problems, motor disorders, epilepsy, and language development problems."

No one can agree whether autism is a single condition, or usually comes as a package deal with other neurological conditions. In this graphic, for example, autism (or Autistic Spectrum Disorder, to give its full title) is bundled in with everything from anxiety to Tourette's.

To give one example, Smaller Boy is dead-cert for getting an Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) diagnosis, if we want one, putting him among 30-70% of the autistic population (statistic varies). In fact, ADHD and autism diagnoses co-occur so frequently that Bigger Boy is in the minority by NOT being AuDHD.

[Personally, I don't think Smaller Boy has two different neurological disorders. He's just an extrovert!]

Why does all this matter?

In 1783, Antoine Lavoisier wrote phlogiston was:

"a view which I consider an error fatal to chemistry, and which appears to me to have considerably retarded progress by the method of false reasoning which it has engendered ... "

Autism, the phlogiston of psychiatry, is now generating the same social and scientific confusion. Originally developed by Kanner in 1943 based on observations of 11 children and by Hans Asperger trying to save (four) gifted boys from the Nazis, it's ballooned into a 'catch-all' for neurodevelopmental conditions we don't yet understand.

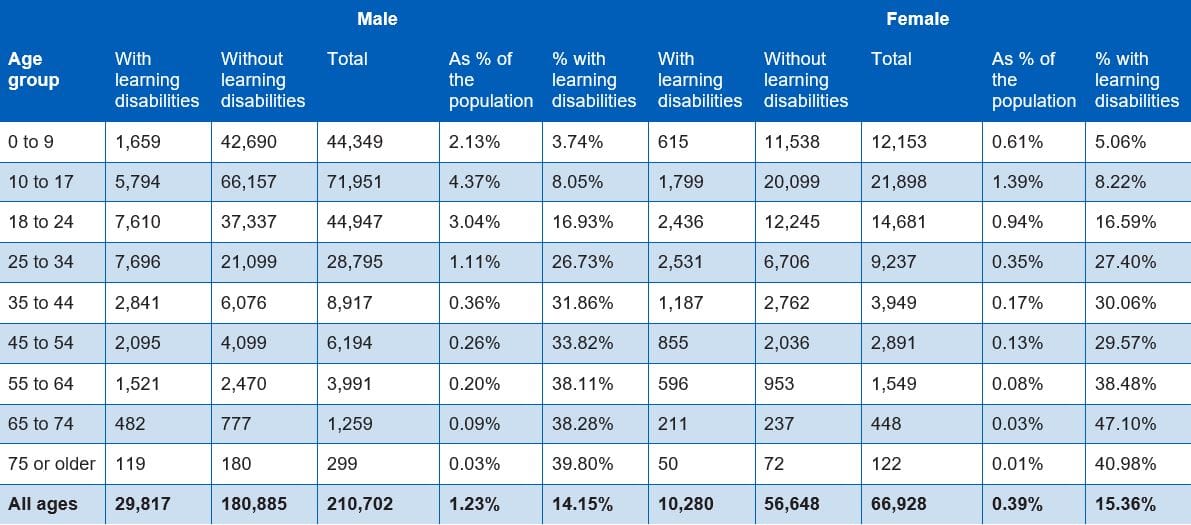

The result is absurd... and devastating. 1 in 31 eight year olds in the US are now diagnosed as 'autistic' with the vast majority, as per UK and US statistics, being kids with less severe disabilities - such as Smaller Boy. Whereas more than a third of autistic men over 40 in the UK have learning disabilities, less than 6% of autistic under-nines do. This implies there's a vast cohort of adults (inc. yours truly) who would have likely gotten autism diagnoses if they were a child again today.

This is clearly a result of more screening and awareness, and not a 'real' increase in cases, but - nonetheless - it's become open season for conspiracy theorists, such as Robert F. Kennedy Jnr., who gave a press conference blaming 'environmental toxins' for an autism 'epidemic' and pledging to find a 'cure' by September. If you've been agreeing with my essay, thus far, you can now laugh quietly into your cornflakes.

Drowning in a sea of nothing...

Robert F. Kennedy Jnr was correct (!!) to highlight the plight of the minority of families where severe inherited genetic disorders lie behind the 'autism' label. There are several disease-carrying gene variants known to consistently produce autistic behaviours with moderate/severe intellectual disability, such as mutations in the SYNGAP1 gene or Fragile X.

In the vast majority of cases, however, the causes aren't yet identified, and families are left without answers - or even a meaningful diagnosis.

Bigger boy's former classmate, Y, had no diagnosis except 'autism'. However, his older brother also had severe intellectual disabilities, as did an uncle on his dad's side. Y's mum had only two kids, as a doctor had advised her that any future children would, most likely, have the same condition as their siblings. Her son, Y, was a sweet, shy little boy who I always worried about. He was always crying and I feared he might be suffering, as I knew Bigger Boy found classroom noise tough. Y's mum had no family support. Her marriage was on the rocks; the couple blaming each other for their boys' disabilities. She wanted another child, but not with him.

When we met in a cafe, me a virtual stranger, she wept in my arms.

No one ever questions scientific research into well-known single-gene conditions, such as Angelman Syndrome, or suggests it's merely a neurotype that parents should embrace. Yet the vast and growing cohort of families like mine, fearful (justifiably) of future eugenicists coming for their children, shut down 'autism' research projects and tell parents like Y's mum to "suck it up, snowflake - just try to accept and understand."

Ultimately, disability is normal. Around 17.8% of the UK population are disabled, and most of us become disabled as we age. All civilised societies should support people who are disabled, because that's a fifth of us. If we're not disabled already, we can become so at any time. There is no conflict between helping Y to live his best life, and also feeling we need the science to meet Y's mum's desire for a child without severe disabilities - as we already do with mitochondrial disease.

That science won't be called 'autism' though.