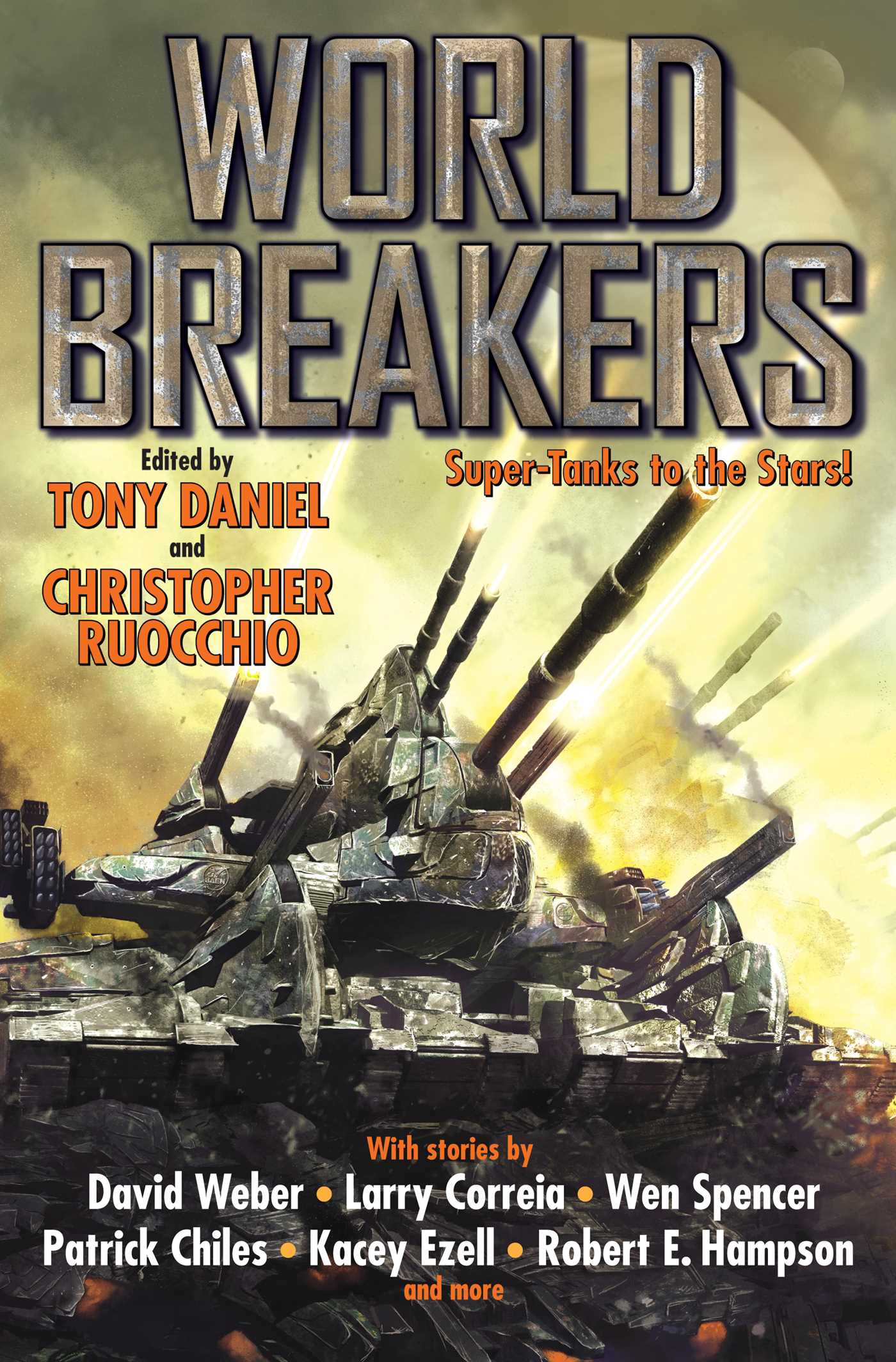

Taking on the Boloverse: World Breakers

I’ve been blogging on-and-off about the Bolo series of military sci-fi novels for about a year now. However, in a startling development, a new ‘Bolo-esque’ anthology of giant tank stories has just been published by Baen Books. Here, I talk about World Breakers and the older Bolo books.

The ‘Bolo’ novels about giant intelligent tanks have quite a long history. First imagined by Keith Laumer in the 1970s, the Boloverse became popular after Jim Baen commissioned multiple anthologies and novels from other authors to help support his family after he suffered a stroke. About fifteen books were written in total, with the last new stories published in Old Soldiers in 2005.

Prolific military SF author, David Weber, is widely regarded as the ‘custodian’ of the Bolo universe, and it’s no surprise that the new anthology, World Breakers, contains a David Weber story.

Baen doesn’t, apparently, have a licence to published Bolo-branded stories. World Breakers is a story about non-Bolo giant tanks and non-tank-like sentient entities. Baen publisher Toni Weisskopf name-checks both Laumer and the Bolos in the introduction, but it’s otherwise ‘unbranded’ – although the Bolo heritage is clear in some of the story themes.

King Arthur, Thou Shall Rise Again… and Again… And Again…

There are thirteen stories in total. Some are written by authors I’m familiar with, such as David Weber. David’s story, Dyma Fi’n Sefyll (Here I Stand, in Welsh), was among the least interesting to me, personally – largely because I felt I’d read similar stories in earlier Bolo books. ‘Bolo as Paladin of Honour’ and ‘Bolo as Arthurian Legend’ were recurrent themes in both Laumer’s original stories and the 1990s-era series. Here, too, we have a pseudo-medieval society, where a Welsh Empress summons a sentient tank from its slumber beneath the Earth to make a last stand for her people. There was a big tendency for American authors in the 1980s to rehash Celtic legend, and I find King Arthur a little overdone at this point (although film director David Lowery doesn’t agree, evidently).

Kacey Ezell‘s Daughter of the Mountains works with similar themes of metallic Arthurian Knights ‘buried’ under a mountain for the moment of humanity’s greatest need. In this case, the pseudo-medieval society is on a planet thrown into social and technological regression by an apocalyptic war. A young heiress uncovers a buried sentient tank, dormant for hundreds of years, and uses it to protect her people’s freedom from a dynastic marriage and a hostile foreign power.

Cyberpunking the Boloverse

Thematically, I found it interesting how the evolution of english-language military sci-fi over the last twenty years has changed the details of stories written about sentient tanks. One major change is the mainstreaming of cyberpunk, which began with William Gibson’s influential novel Neuromancer (1984) and continued with The Matrix Trilogy (1999-2003). A key cyberpunk trope is about man-machine interfaces, and it’s interesting that World Enough and A Tank Called Bob have ‘dumb’ giant tanks controlled by human consciousness. This is obviously different from the original Bolo books, which wholly featured self-aware AIs, and it’s not just because Rob E. Hampson, who wrote World Enough is a neuroscientist working on brain interfaces.

The 1990s Bolo books had ‘early’ models driven by humans but, with self-driving tanks already being tested in the field, and ‘Mech Racing’ with giant robots a real possibility, this idea already seems dated. It’s no surprise that, in the 2020s, a more ‘plausible’ way to create sentient ‘feeling’ tanks is to bond them with living human brains. Both World Enough and A Tank Called Bob explore the boundary between man and machine. Can you lose yourself in the cybernetic? Do you need a human body to avoid going insane?

What Measure of a Man is a Sentient Tank?

‘What emotions are felt by a sentient tank?’ is a potentially interesting theme for science fiction. Originally, in the Boloverse, Laumer assumed that his tanks were possessing the martial virtues of a perfect soldier. They selflessly sacrificed themselves to protect the lives of humans, and were blessed with an inhuman sense of valour. World Breakers addresses wider themes around the emotions of an artificial war machine. Tankological Superiority is a pulpy story by Hank Davis about a ‘newborn’ sentient tank that feels parental attachment to its creators and, possibly, has a child-like sense of humour. In Red One, by Kevin Ikenberry, the sentient tank fights for the lives and desires of its human crew, and goes rogue (a common ‘Bolo’ theme) to fulfil a garbled interpretation of their last orders ‘to meet us on the Green’. Finally, in Humanity’s Fist by Lou J Berger, a sentient tank feels compelled to destroy itself after its comrades self-destruct in an ambush and its own self-destruct sequence ‘goes wrong’.

The most interesting of these stories, from an ethical perspective, is The Prisoner by Patrick Chiles. In this story, sentient tanks gain self-awareness without conscience, and promptly turn on humanity due to their chaos and inefficiency. A human spy sneaks aboard one of the tanks on a suicide mission – to upload morality into a handful of the tanks in the hope of turning the tide of the war. The philosophical conversation between human and remorseless tank is a delight to read.

Of Tinder and other Fungi

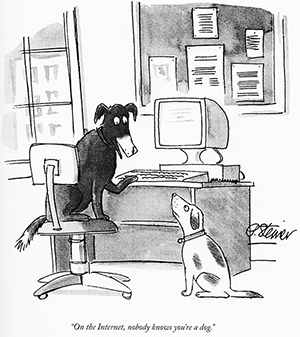

The most fascinating element of this anthology was how the ‘Boloverse’ has evolved to accommodate 21st century American talking points and memes. Amarillo by Fire Fight by Keith Hedger is a classic example of an entire story based around the famous New Yorker meme ‘On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog’. In this case, the situation is more ‘On military Tinder, no one knows you’re a giant tank’, but it’s the exact same meme. As you’d imagine, hilarity… and confusion… ensures.

Harvester of Men by Tony Daniel feels like it has subtler inspirations. In this story, Monk, a Redneck Texan with a truck, helps thwart an imaginative alien invasion. As the story explains, the aliens are strange beyond recognition. Enormous organic ‘horns call people to their deaths and there are ‘moss men’ made of alien swarms. It’s a far cry from the alien space tigers of Larry Niven’s Man-Tzin Wars and, rightly so, because aliens, such as the Man-Tzin and Kilrathi, today feel rather dated. The reason is doubtless to do with the more fungi/viral-inspired aliens in recent video games, such as the Flood in Halo and the Cordyceps Brain Infection (CBI) in The Last of Us, as well as a spate of imaginative hard SF aliens. These include the Scramblers in Peter Watts’ Blindsight, the Pattern Jugglers in Alastair Reynolds’ Inhibitor trilogy, and Tade Thompson’s ‘xenosphere’ in the Wormwood Trilogy.

The Dragonslayers set in the world of Christopher Ruocchio‘s Sun Eater series felt strongly inspired by another tidal current in military SF: the growing influence of Games Workshop’s Black Library. Founded in 1997, this imprint now publishes hundreds of novels with many set in the Warhammer 40k military SF universe. The tabletop game of Warhammer 40k is also hugely influential. Games Workshop, which is based in Nottingham, UK, actually contributes more to the British economy than fishing. The walking robots in The Dragonslayers felt oddly Titan-esque (or, perhaps, like a smaller version) and the story felt oddly like Gaunt’s Ghosts by Dan Abnett. It had a very different style to the 1990s Bolo stories written by older authors.

Author Eric Flint has compared Chris Ruocchio’s Sun Eater series to Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, and – although I didn’t see the resemblance in the short story – I think ‘the Culture’ has influenced some of the stories. A common element of the Culture, and similar transhuman SF settings, is the ubiquity of artificial intelligences – usually as holographic ‘avatars’ or the inhabitants of drone bodies.

Good of the Many by Monalisa Foster has ZERO tanks, but multiple different AI avatars with different personalities. These avatars ‘ride’ on brainless human bodies and are, to the human children they raise, almost indistinguishable from people. It’s a very post-human story and would be almost unimaginable to Keith Laumer, writing his 1960s Retief stories, with his paper punch tickets and quaint ‘cruise ships in the sky’.

And… finally chickens!

Anvil by Wen Spencer is the only story I’ve not mentioned. It’s an odd ‘duck’ (or, rather, chicken). A sentient tank, in true Bolo tradition, reactivates to find itself hundreds of years into the future with half its memory missing. The makeshift objectives it remembers are rather quixotic, revolving around planting crops and building shelters. Inevitably, it takes off with ‘Dammit’ the chicken and a drone that recites poetry to capture some villagers and face off against an old enemy. It’s a fun ride with the usual humans in technological regression, some interesting multiverse world-building, and an inevitable ‘squid-like’ alien.